Ephraim Sechrist began renovations on the distillery after Repeal on December 5, 1933. He added a 3-story brick bottling plant north of the distillery and returned modern equipment to the still house. In August 1935, the federal authorities were making their final inspection of Sechrist’s renovated buildings, now called the Lebanon Valley Distillery. The distillery began operations, but complications that included the advent of WWII shut down production and set back progress. In 1942, Ephraim Sechrist was killed in an auto accident in Lebanon, Pa. He was seated as the passenger as his son drove when they were struck by a truck loaded with defense materials. Ephraim’s widow, who also survived the crash with her son, sold the distillery to Louis Forman soon after her husband’s death.

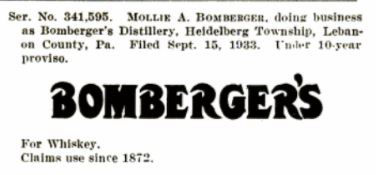

Louis Forman was a liquor broker in Philadelphia that had his eye on the distillery since he surveyed the property in 1937. Unfortunately for Louis, the year he came to own the distillery, he was drafted into the military (US Navy). Unsure of his future, Louis sold the distillery to some Philadelphia investors who later became the Logansport Distilling Company. In 1946, they demolished the Bomberger’s farmhouse and replaced with a 100-foot distilling tower and cistern building. A new grain facility, a separate fermenting and granary building, and a machine shop were added, as well. Meanwhile, Louis Forman had returned to Philadelphia after his military service, reassumed his role at his liquor brokerage where he continued to expand his holdings. On November 11, 1947, The Logansport Distilling Company sold the property to Schenley Distillers Corporation. Schenley clearly did not place much importance on the property because less than three years later, in April of 1950, they sold the distillery to Kirk Foulke. Foulke changed its name to Kirk’s Pure Rye Distillery Company. Louis Forman, who had never lost his interest in the property, partnered with Foulke, and regained his control of the distillery. They began immediate renovations. 2 large cement block aging warehouses were built, each able to house 20,000 barrels. Much of the existing original construction (distillery, warehouse, and jug house/retail house) was maintained and repaired. It was during this renovation that Louis Forman came across the treasure trove of Abraham Bomberger’s records from before Prohibition. The discovery of these historic references redirected Forman’s focus toward historic preservation and influenced his Pennsylvania Dutch themed marketing.

Louis Forman hired Charles Everett Beam as master distiller and consulted Beam throughout product development. Together, they created a niche market making old fashioned pot-still mash whiskey that he sold in porcelain crocks. The recipes and jug yeast fermentations claimed to follow the tradition of the Bomberger distillers, but as with most modern whiskey advertising and marketing, it only very loosely applied. The recipe decided upon by the men for their “sour mash pot still” whiskey recipe was 38% rye, 50% corn and 12% barley. It was not a bourbon, so they had more leeway in their production process. Used cooperage, for instance, would be much more cost effective. Forman began his first batch of Michter’s pot still whiskey in 1951, but in the six years it took to age, he found his new business in the throws of a recession. Toward the end of the decade, Kirk’s Distilling Company, Schaefferstown, was sold to Pennco Distillers, Inc. for $60,000. Ownership was transferred in a deed and placed on record on January 10, 1958.

Forman maintained his ownership of Michter’s whiskey formula and the stock of sour mash whiskey he had aging in Pennco’s warehouses. While Pennco Distiller’s Inc. kept the business running by doing contract distilling of rye whiskey for companies like Old Overholt and Wild Turkey, Louis Forman was able to sell Michter’s as a specialty item. On March 10, 1971, Forman was named president of Pennco Distillers, Inc. After 30 years, Forman was finally at the helm again. By 1972, Forman had a new $200,000 bottling plant up and running and new storage tanks installed that held 12,800 gallons each. C.Everett Beam, now vice president in charge of production, was getting ready to retire after over 20 years with the company. Beam’s well-trained protégé, Dick Stoll, was positioned to take over as the facility transitioned again. The distillery was on its way to becoming as much a tourist destination as it was an industrial production plant.

Pennco maintained ownership of the distillery until 1975 when they sold the property in a foreclosure sale. Louis Forman, with the help of some Lebanon Valley businessmen, purchased the plant and reorganized the company as Michter’s Distillery. The name Michter’s may sound very Pennsylvania Dutch, but it was actually the melding of Louis’ sons’ names- Michael and Peter. To celebrate his newly christened Michter’s, Forman commissioned Vendome Cooper & Brass Works in Louisville, Kentucky to construct two copper pot stills, a worm tub condenser and cypress fermenters to be installed in the property’s original still house. Louis Forman would finally have his historic whiskey distillery of a bygone era. Though the main production facility would continue to run a large column still and doubler to produce Michter’s whiskeys, the copper pot stills would run daily for the tourists and produce one barrel of pot still whiskey per day. On the year of America’s bicentennial, the distillery was named to the list of National Historic Places. In June of 1980, it was designated a National Historic Landmark by the Department of the Interior. Officially the oldest distillery in America, there was no other in the United States producing whiskey in a similar manner. The Historic Landmark designation also came with perks. The distillery could sell directly to the public on premises seven days a week! The sales were made in Michter’s Jug House (the original Bomberger’s retail house) which also served as home to Michter’s International Collector’s Society. Collectible bottles and decanters, many of which celebrated local history, were sold directly to tourists and Society members. By 1985, the distillery was the first to accept credit card sales and the first to be able to ship full liquor bottles and decanters via UPS throughout the state of Pennsylvania. These unique sales opportunities for Michter’s Jug House set the precedent for the adoption of new, state-wide laws applying to Pennsylvania’s craft distilleries over 30 years later.

One of the enduring legacies of Michter’s remains its connection to Lebanon and Lancaster County’s local economies. Not only did the distillery serve as a large tourist destination, but it also supported local farms by purchasing large amounts of corn and rye from area grain producers. The distillery relied on four kinds of raw materials: rye, corn, barley malt and limestone well water. The rye grain used was a specialty varietal called Rosen rye which was initially sourced from Michigan but was later supplemented by local producers. The barley malt was shipped in from Wisconsin in the early 1970s and later sourced from North Dakota’s Red River Valley. The corn was grown locally by farmers that could meet the distillery’s grain quality specifications. In 1971, records show that over 120,000 bushels of corn, 50,000 bushels of rye, and 25000 bushels of barley malt were used in whiskey production. Pure limestone water was tapped from deep wells reaching though 3 limestone ledges: the Buffalo Springs, Snitz and Schaefferstown ledges. The calcium carbonate rich water that was pumped from the wells beneath the distillery maintained a constant 54 degrees Fahrenheit. The limestone water below Michter’s remained an enviable resource even after the property closed to the public. In fact, in the 80’s, some Kentucky distilleries looked into the possibility of drawing off the water for their own use.

Over the course of the next decade, sales fell from 40,000 cases to 10,000 cases sold annually. In 1989, Michter’s was producing 50 barrels of whiskey per day, six days per week, 3-4 months (beginning in late fall) of the year. It was the last functioning whiskey distillery in all of Pennsylvania. It came as a surprise to Dick Stoll when he was instructed by the bank on Valentine's Day 1990 to shut everything down and lock the doors. The distillery would not reopen.